ABOUT US

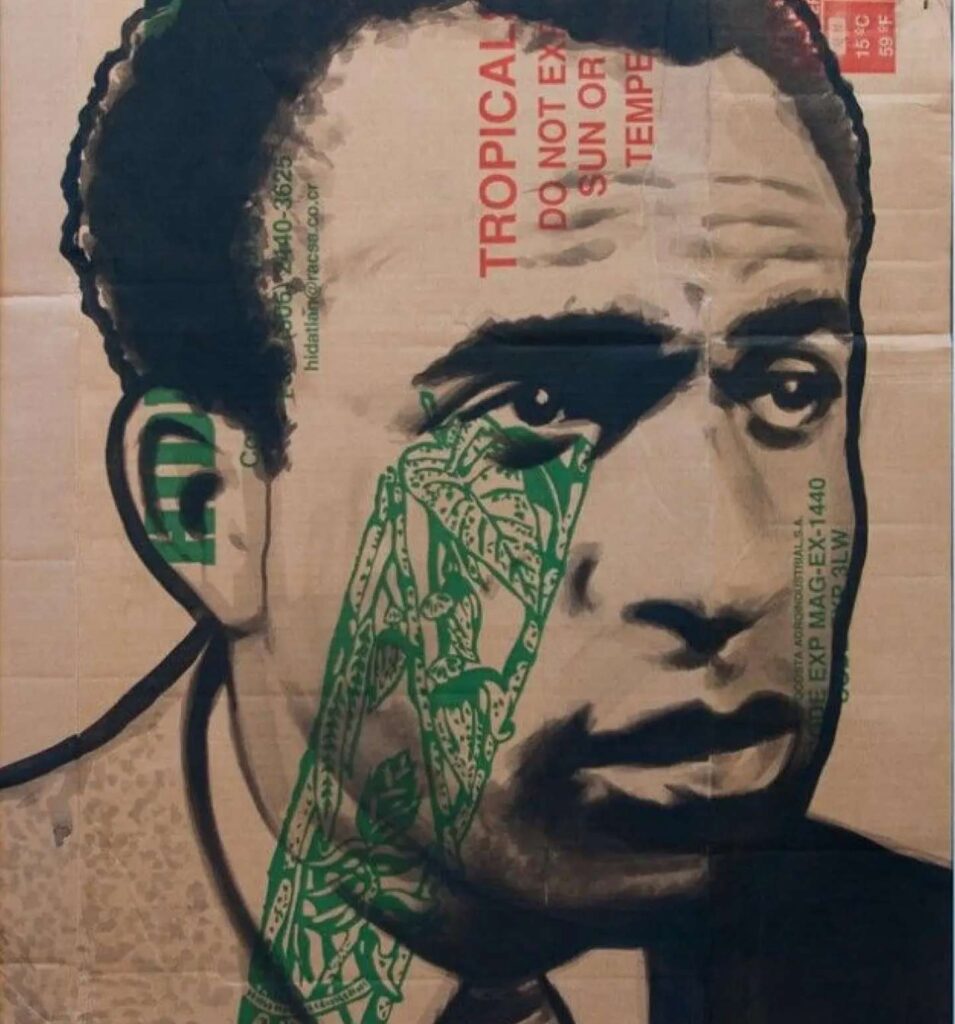

Frantz Fanon

ABOUT US

Frantz Fanon

Fanon was born in Martinique, a French colony, on July 20, 1925, into a middle-class family. He attended high school where his teacher was Aimé Césaire (1913-2008), the famous poet of Cahier d’un retour au pays natal and Discours sur le colonialisme, a leading figure in the négritude movement.

After taking part in World War II, fighting first with the British Resistance and then with the French Resistance, he enrolled in medical school in Lyon, where he graduated in 1951. The following year, he began working as a psychiatrist, first in Saint-Alban—where Francisco Tosquelles, a Catalan psychiatrist, was experimenting with the first forms of deinstitutionalization (his model of “institutional psychotherapy”)—then, after moving to Algeria, in the psychiatric hospital in Blida. Here he was able to observe firsthand the dramatic consequences of colonial oppression and the effects of torture practiced by French forces on militants of the National Liberation Front (FLN).

After three years, he resigned, declaring it impossible to reconcile the therapeutic goals of his profession with the social and political role he found himself playing as an employee of the colonial administration. With this gesture, Fanon began to confront directly what he felt was an urgent need to act, committing himself personally to the anti-colonial struggle. In 1956, when colonial repression in Algeria became particularly violent, he joined the National Liberation Front and actively participated in the struggle. This choice cost him expulsion from the country by the French authorities, but it did not stop his political and educational commitment within the context of the war. He then settled in Tunis, where he began intense diplomatic and political activity. He was a member of the editorial staff of the FLN’s press organ, El Moudjahid. He was ambassador of the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA) in Ghana, carrying out important missions in several African states and meeting the protagonists of the anti-colonial struggles of those years. Having escaped several assassination attempts, he died of leukemia at the age of 36 on December 6, 1961, in Washington. He was buried in the Chouhada cemetery in Tunis a few months before the proclamation of independence.

Famous in the 1960s as a theorist of liberation movements, Frantz Fanon was a keen scholar of the mechanisms of mental and cultural alienation characteristic of the “colonial situation” (Balandier). Raised within the Enlightenment and universalist ideals of French culture, he experienced its contradictions and hypocrisies firsthand, offering in his writings illuminating insights that are now regularly taken up by postcolonial studies and subaltern studies (Said, Gilroy, Guha, Bhabha, Mbembe, etc.). His corrosive analysis of certain literary works of the time and his criticism of some famous psychiatric and psychoanalytic works (by John Colin C. Carothers and Octave Mannoni, in particular) place him among the most acute pioneers of this field of study. His efforts, inspired by psychoanalysis, phenomenology, and Marxism, spare no one, neither the national bourgeoisies emerging at the dawn of national independence, nor the European intellectuals who are also committed to the anti-colonial cause: “Why write this book? No one had asked me to, least of all those to whom it is addressed. So? So, calmly, I reply that there are too many imbeciles on this earth. And since I say so, it is a matter of proving it” (Fanon, Peau noire, masques blancs, 1952, Seuil). His writings scrutinize the gray areas of the colonial context, the ambivalence of the colonized (the so-called ghosts of “milkification” among black people), the dual narcissism of whites and blacks alike (which led him to distance himself from the négritude movement), the reproduction of racist stereotypes in the very places of care and in those fields of knowledge (medicine and psychiatry, first and foremost) that do not hide their complicity with colonial rule, even in its most brutal aspects (Fanon denounces the role of doctors in torture). Among the central themes of his thinking is that of “recognition” and the need not to be crushed by the weight of the past: “The analysis of the psychiatric categories coined from time to time to classify, diagnose, and define the cultural Other is not only of historical interest: it is necessary to explore their genealogy and long-lasting effects (the primitivist paradigm, for example) in order to understand the roots of contemporary epistemological conflicts and the controversies that run through contemporary ethnopsychiatry. In opening up this new horizon, which is epistemologically more accurate and politically more sensitive, the work of Frantz Fanon represents a decisive step: with him, and in the works that will soon be published in various countries, we can recognize (alongside the critique of colonial psychiatry) the origins of a genuinely self-reflective ethnopsychiatry (i.e., one that considers not only models of illness and treatment in other societies, or the influence of culture on behavior, but also the categories of Western psychiatry, the ideology that nourishes its models and practices). However, a psychiatry capable of liberating man, capable of making him feel at ease in his living environment, as Fanon wrote, could not be achieved in a context characterized by violence, torture, and alienation, in a situation such as colonialism, which sought to deny the very humanity of the colonized. Fanon’s choice speaks to this impossibility’ (Beneduce, Etnopsichiatria. Sofferenza mentale e alterità fra Storia, dominio e cultura, 2007, Carocci, Rome).